|

Dear Mystery Fans,

My new mystery novel, Mars Hill Murder, will be published this fall! It’s a story based in Flagstaff, Arizona, and follows two plot lines. One focuses on people getting murdered by an unknown killer wielding a knife. The other is about a woman, 30-something, fleeing from her past. But what—or who—in her past has her on the run? A journalist, Miles Harper, is covering the murders when he meets that young woman, Madeline Sullivan, and they become fast friends. Could it be more? Madeline is traveling with her fuzzy pooch Daisy, who wins hearts wherever she wags. Many other characters help tell the story, set in 2010. Why not read Mars Hill Murder to meet these other unique players in this mystery novel? I’ll let you all know when the book hits the bookshelves and digital book world, so you can see what happens with Miles, Maddy, and the murders in this mountain town. (How ‘bout that for some serious alliteration?) Stay tuned. While I am now focused on creating fiction rather than journalism, I still hold close to my heart all the gun-violence survivors I met and interviewed. Thank you.

0 Comments

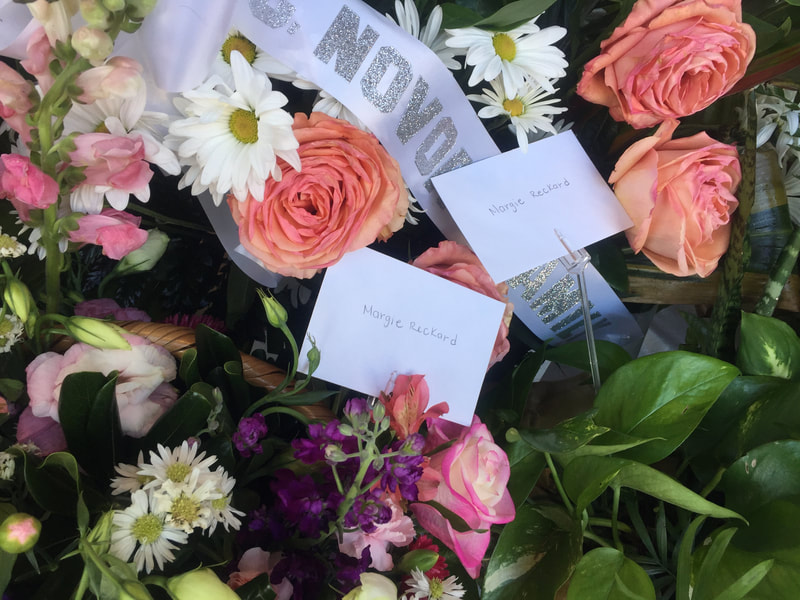

Mary Tolan Mary Tolan Dear blog followers, I need to step back from The Ripple Effect: Stories of Gun Violence Survivors blog, so I can devote my time to other kinds of writing — still about survivors of gun violence. Also, since I am back at my full-time teaching job in Flagstaff, I am not traveling as much across the country to meet with survivors as I did during the past year. So, while I still have hours of audio to transcribe, I won’t be doing new interviews for a while now. This is not a good-bye, but a thank you: To all the survivors who shared their heartfelt stories with me over the past year. I always have you close to my heart. I will not forget you and the journeys you are on. Since launching this blog on the first anniversary of the Marjory Stoneman Douglas High School shooting in Parkland, Florida, I have met so many wonderful people. And to you, readers, thank you for giving me feedback and cheering me on as I shared the moving stories of others. Since June 2018, I traveled thousands of miles to nearly a dozen locations across the country, talked with approximately three dozen survivors of gun violence, and interviewed people for nearly 100 hours. I talked to survivors in their homes, at coffee shops, in libraries and restaurants, and sitting in the sunshine at public spaces. I was touched by how many of you let me into your lives. I watched the tears come with your story telling, the anger come from the violence of the shootings, and the warmth come from your hearts. While this blog is on hiatus, I will still post from time to time, and hope by next summer to give you an update on my other writing — still focused on survivors of gun violence. Stay tuned. Meanwhile, I hope you stay safe, engaged, and in the now. August 3, 2019, a young white supremacist intent on killing Hispanics committed a mass shooting in El Paso, Texas, leaving 22 people dead and 24 injured. Only four days later, a different white man parked his pickup outside a community center in El Paso, pulled on blue latex gloves, garnished a knife and revealed a gun in his truck. Members of the mostly Hispanic Casa Carmelita community center, still on edge from the shooting, called the police. According to news reports, the young man’s truck displayed a large banner showing President Donald Trump brandishing an assault weapon, Rambo-style, and bumper stickers promoting InfoWars, a far-right conspiracy website and radio show. The man arrived the same day Trump visited El Paso in the aftermath of the El Paso Walmart shooting. The police responded, questioned the man, and soon released him about a block away from the center, news reports said. The man told the police and media that he was on his way from Houston to a right-wing gathering in Portland, Oregon, when he decided to stop at the El Paso center. Police said he had broken no laws. Guillermo Glenn, a long-time labor organizer and activist in El Paso, said he has experienced racism for many years, and is not usually surprised by it. But he added that he was caught off guard by the mass shooting. “The shooter did surprise me. The manifesto surprised me. I mean, we’re used to some violence here. And we shouldn’t be used to the institutional racism we got,” he said, laughing as if to say, “But we are used to it.” Glenn, 78, was in Walmart when the gun shots began, and he helped carry wounded people to paramedics. He noted the existence of white-supremacist camps on the outskirts of El Paso, which he said could mean additional racist shootings focused on brown-skinned people. “I think [there’s] gonna be more,” Glenn said. “And I don't think the city, nor are the agencies really preparing for that. The attorney general in Texas says, well, the solution is that we should buy more guns so everybody can be packing. It was his solution. This is pretty bad.” Glenn came directly to La Mujer Obrera (The Woman Worker) organization and community center after the shooting and read the shooter’s manifesto with others. La Mujer Obrera is in the heart of El Paso’s Chamizal, mostly Hispanic, neighborhood. Another El Paso activist who read through the shooter’s statement with Glenn the day of the shooting was Cemelli de Aztlan, an outspoken El Paso Latina activist. She said institutional racism has long been a reality for El Paso Hispanics. She also said that the second white gunman who visited El Paso that week was likely focusing on another local activist. De Aztlan works with the El Paso Equal Voice Network, a group of community organizations working for low-income El Pasoans. She said earlier in the year El Paso organizer Ana Tiffany Deveze had been entered into police records, which were distributed nationwide. Deveze and other protesters were charged after a February 2019 incident in which they put up anti-immigration-policy stickers at the National Border Patrol Museum in El Paso. “To put her mugshot alongside murderers, thieves, wife-beaters, and to brand her as one of El Paso’s most wanted,” de Aztlan said. “That’s what they did to her.” De Aztlan said the the Border Patrol released a press release sending out names and zip codes of people arrested for vandalizing the museum. The February activists were accused of causing more than $2,500 in damage to museum exhibits by gluing stickers with photos of migrant children who died in Border Patrol custody, according to media reports. “It was like an invitation to every white supremacist to come and visit them,” De Aztlan said. “Why do we even have a Border Patrol Museum?” For some people in El Paso, Texas, a mass murder of brown-skinned people by a racist white man was not as shocking as the public seemed to think. DeAztlan said for Hispanics in this city, poor treatment from people in authority including law enforcement is nothing new. “This is the highest populated neighborhood of immigrants, ” De Aztlan said over a plate of steaming cactus rellenos in Cafe Mayapan, located in La Mujer Obrera. The organization and center focuses on Hispanic history, stories and power. La Mujer Obrera was created in the 1980s to support mostly Hispanic El Paso garment workers. With the signing of the 1994 North American Free Trade Act, however, many of those workers lost their jobs. NAFTA is a trade agreement between the United States, Mexico and Canada. Several El Paso factories were shut down, and a 2014 study found that the agreement meant more than 800,000 people in the U.S. lost their jobs. Several women who work at La Mujer Obrera center and Cafe Mayapan restaurant were retrained after being displaced. De Aztlan criticized destructive NAFTA’s destructive nature, saying that it devastated El Paso Hispanic workers. “It tore the base of this community, the economic base of this community,” she said. “And it literally sent the message that these women were disposable.” The La Mujer Obrera celebrates the dignity and diversity of the Mexican heritage. This includes the low-price authentic Mexican-food restaurant, a space for art exhibits, day care, and training in the restaurant. The center’s mission includes pushing for community health and civic engagement. “Many people from my generation feel like it’s the mother hen of our community,” said de Aztlan, 38, who added that as a girl she and her sisters used to hang out in the center with their parents and later on their own as teenagers. “So I love it here.” While El Paso is nearly 85 percent Hispanic, most of the people in political power are Anglo. Many policies put forth by the current administration and other leaders past and present “have been anti-immigrant, have targeted the poor, have disenfranchised and dismantled those communities,” de Aztlan said, and Glenn agreed. There may not be a direct link between disenfranchising policies and the mass shooter who came to an El Paso Walmart, but de Aztlan said it was unsurprising to a community of Hispanics who are often abused by those in power, and who feel constantly harassed by “police or ICE hanging around.” “The top priority is that … we want safe communities. But the way to invest in safe, secure communities is to invest in families, invest in the poor,” she said. “People talk about how, you know, we're all community, [but] we’re like huddled in the attic.”  Lonnie and Sandy Phillips Lonnie and Sandy Phillips Sandy and Lonnie Phillips have taken to a life on the road after their 24-year-old daughter was shot dead in a movie theater in Aurora, Colorado, June 20, 2012. Jessica “Jessi” Ghawi, who dreamed of becoming a sports broadcaster, was with a friend at a midnight showing of the movie “The Dark Knight Rises.” When a gunman threw a smoke bomb into the theater, chaos broke out and the gun shots began. Ghawi died from multiple gunshot wounds. She was one of 12 people killed; another 58 were injured by gunfire. Fewer than two months earlier, she had barely missed being shot. In a Toronto mall, a gunman shot two people dead where Ghawi had just been. She later told her mother she had been standing exactly where one of the shooting victims died, just minutes earlier. Lonnie and Sandy Phillips said they have learned this kind of story is not longer unusual. “We now have subclasses of public mass shootings,” Lonnie Phillips said. “Now we have the second person that survived Las Vegas and was murdered in Borderline cafe.” Telemachus Orfanos was among the festival goers who survived the Route 91 Harvest music festival in Las Vegas Oct 1, 2017. The shooting left 58 dead and more than 400 wounded. Approximately a year later, Orfanos was one of the 100 people inside the Borderline Bar & Grill in Thousand Oaks, California, Nov. 7, 2018, when a gunman opened fire. Orfanos was one of 12 people killed; another dozen were injured. Some of the California residents who survived the Las Vegas shooting regularly gathered at the Borderline to listen to country music, dance and support one another. Orfanos’ father was quoted in the press at the time, blaming his son’s death on the gun culture. The Phillipses had more examples of people experiencing multiple shootings, because they have met so many survivors. “And then we have the young lady, this young lady that was not wounded, but was at the shooting in Las Vegas and was so traumatized by that that she wouldn't go out in big public spaces. And finally went to the Gilroy Garlic Festival and was there to witness that,” Sandy said. A man shot and killed three people and wounded 17 at the festival in Gilroy, California, July 28, 2019. “So, you know, this is happening more and more. We know one woman that lost all four of her children to gun violence, but in different years. We know another woman whose two children [were shot and killed], 20 years apart. She was actually pregnant with her son when her daughter was killed. And 20 years later, he was killed in a robbery.” Lonnie said these kind of odds should help people realize something must be done about gun violence. “When we think of in that sense, you have to realize since with these coincidences, the odds against that happening to two people, the same thing missing a mass shooting and even killing and another that then has to be able to resonate with people that ‘God, this is happening so often. It can happen twice to two people.’ But they still do not believe that it could ever possibly happen to them. It's just human nature.” Sandy and Lonnie said they were also complacent about shootings before Jessi was killed. “Until it happens to them, they are not going to be involved in thinking it. That’s what happens to other people,” he said. “Problem is trying to convince people that this could very easily happen to you. It's just, no one believes it. It's too, it’s like getting hit with a piece of space junk.” For the Phillipses, the pain and sorrow of Jessi’s murder never goes away. But after the Sandy Hook shooting happened just six months after the Aurora shooting, they traveled to Newtown, Connecticut. They wanted to see if they could be of any help to those parents whose children were also murdered by a gunman. After that, they knew this was their path. Sandy and Lonnie Phillips decided to commit themselves to helping others who were experiencing the loss of a child or other loved ones after a mass shooting. One element the Phillipses and other survivors address is language. Sandy said she does not agree with using phrases that somehow lessen the impact of a person’s death, and they stress that when they work with other survivors. “If you're using [a phrase] like ‘my son, I've lost my son.’ No, you didn't ‘lose’ your son. Your son was brutally taken from you,” Sandy said she counsels survivors. “He was murdered, slaughtered. Whatever word you want to use. But tell it authentically and honestly.” Some days, Lonnie and Sandy Phillips drive their Ford F-350 through the mountains or desert, and don’t talk. Pulling their camper behind them, they often need hours of silence to get a reprieve from the work they do. The work they embraced not long after the worst day of their lives. Their daughter, Jessica Ghawi, an aspiring sports broadcast journalist, was murdered in a movie theater in Aurora, Colorado, July 20, 2012. Almost immediately after the killing, the couple knew they needed to do something to fight gun violence. Every year, they put thousands of miles on their truck as they travel from one public mass shooting to another, trying to bring solace to the newest members of the “family” of survivors. They offer their knowledge of and experiences with grieving. It may not make the survivors’ loss any less, but it is the Phillipses hope that their visits and words can make the survivors’ immediate future a little less frightening or confusing. Jessi, 24, and her mother had texted that night, and Sandy knew her daughter was with a friend at a midnight showing of The Dark Knight Rises. Lonnie was asleep in their bedroom. “I couldn’t sleep that night for some reason, and had gotten up. And Jessi and I had texted, and then the phone rang and it was [Jessi’s friend] Brent,” Sandy recalled of the night she can never forget. She was surprised. “It was like, ‘What is he doing calling me?’ And I picked up the phone. And then life was over as I knew it,” she said. “I started screaming.” Lonnie woke to the screams, thinking someone had broken into their home. “When I heard her screaming, so guttural, so animal-like, I knew something was absolutely wrong,” said Lonnie Phillips. “I went to find whoever was attacking her, and to help her, and found her sliding down the wall screaming, ‘Jessi’s dead. Jessi’s dead.’” Lonnie carried her to the couch, and tried to understand what she was telling him. “I started questioning her,” he said, saying he soon realized Jessi must be dead. “Because Brent is a paramedic, and he knows that she didn’t have a chance.” Still, they clung to a sliver of hope. They called their son Jordon, and he rushed to their San Antonio, Texas, home. He, too, questioned the veracity of the claim that his baby sister had been shot to death. After hearing the details, he excused himself and went outside. He called Brent. When he came back into the room, he was subdued. He confirmed that Jessi had been murdered in the Colorado movie theater. The next day he flew to Colorado. While the couple was numb for months, it was soon clear that they needed to take action regarding the grisly results of gun violence. “She says, ‘You know we’re gonna get involved in this, don’t you?’ And I said yes,” Lonnie said. “Jessi would have been very upset if we hadn’t done everything that we could possibly do to stop this carnage.” Like many couples who have been together for several years, Sandy and Lonnie often finish each other’s sentences or thoughts. “Stop the carnage. But also to help other people,” Sandy added. “When this happened to us, there was nobody to help us. We were in San Antonio, and it happened in Denver. So we were kind of, like, ‘What do we do?’ And feeling very alone, like nobody else had been through this.” Even though many people had, of course, been through similar gun-related tragedies and gruesome deaths, the couple felt isolated. “It was like, why isn’t somebody reaching out, or how do we find them?” she said. “And so as we started finding out what to expect, most of which was not much fun, we started going, ‘Wow. Wouldn’t it be nice if we had somebody holding our hand through this?’” Five months after Jessi was killed, tiny children at Sandy Hook Elementary School were gunned down in Connecticut. Sandy and Lonnie Phillips traveled there to offer their help. “Those parents walked into the community center that we were meeting at, and I saw their faces and the shock, and the disbelief, and the zombie-like — I knew then,” said Sandy. “I knew then this is what we’re meant to do. That was us five months ago. If we can help these people in some way, we’re gonna do whatever it is that we can to help them. And that started it, and it is just continuing on since then.” They have been to dozens of mass-shooting communities since Sandy Hook, meeting with countless survivors to help them prepare for what might come, and to encourage them to get trauma therapy. Their support group is Survivors Empowered. Though it is excruciating, when speaking to the media or at public gun-reform events Sandy describes the carnage to her daughter’s body caused by the assault-rifle bullets that riddled it. That is so people can truly understand the trauma that bullets cause. “Her right leg was ripped apart and rammed into her left leg,” Sandy reported quietly. “Her abdomen received four bullets and additional fragments. Fragments were lodged in her right wrist and other places. Her left clavicle was broken by a bullet. In her head, a bullet left a 5-inch hole. The bullet entered through her left eye, ripping apart her brain.” In a devastating twist, just seven weeks before she was gunned down, Jessi had just missed being shot in Toronto. She had been at a food court and left to get some fresh air. Three minutes later, a gunman arrived at the same place, killing two people, one of whom stood where Jessi was just minutes before. Jessi blogged afterwards about the importance of living in the moment, and of hugging loved ones. When Jessi called her mother to tell her what had happened, Sandy reassured her. “You have seen the worst of humanity today,” Sandy told her daughter. “You will never see it again.” Not two months later, Jessi, 24, was dead. After visiting the El Paso mass shooting survivors last month, the Phillipses drove north to Colorado, carving out a few hours along the way to find quiet, to be in nature, and recharge. Before the next one.  Thousands of people came and hundreds of flower arrangements were sent to public El Paso funeral. Thousands of people came and hundreds of flower arrangements were sent to public El Paso funeral. Three weeks ago, thousands of citizens of El Paso, Texas, filled the Southwest University Park to listen to community and religious leaders from both sides of the Texas-Mexico border assure them love would win over hate. I joined them that warm night. People lined up for hours waiting to get into the memorial, which honored those people killed in the August 3 mass shooting by a white supremacist who targeted Hispanics. El Paso is more than 80 percent Hispanic. He shooter murdered 22 people shopping at Walmart, and injured about two dozen more. Less than 24 hours later, a different perpetrator killed nine people and injured 27 August 4 in Dayton, Ohio. On the baseball field luminarias glowed — nine white circles commemorating the Dayton victims, and 22 stars in honor of those killed in El Paso. Texas Gov. Greg Abbott said battling white supremacy would be a priority for state police. He announced the creation of a group to battle domestic terror. A large electronic screen showed photographs and short bios of those killed in the El Paso shooting. Some of the survivors were in the crowd, weeping, remembering. Other people came to support them and their families, and to show the heart of El Paso. Normally the stadium is home of the Chihuahuas, a minor league baseball team and Triple-A affiliate team of the San Diego Padres. Andrew Wise, 28, said a friend’s grandmother was killed at the Walmart. He said he was there for that family, but also for all the Texan and Mexican grieving families. “Just being here, just having everybody to support each other really shows how tight knit this city and community is with each other,” said Wise, who works for the Transportation Security Administration (TSA). “And how much we want to just lift each other back up.” He said the shooting shattered the sense of safety in this Texas border town where many Mexicans come to shop and visit relatives. “Of course, you never want to see any city or any families go through something like this, and you always hope that it never comes to your city,” said Wise, who was born and raised in El Paso. “When it hits home directly, it gives a whole bunch of different meaning and a whole — it hurts a lot worse when it gets right up close to home. “And El Paso being one of the safest cities,” he told me, echoing what many said that week. “You think that we’re gonna be always safe. And as soon as somebody came and did this tragedy to us, now, like, our guard is higher. Our awareness is up. Everyone’s on edge. It just destroyed our sense of security. Like, everyone jumps at any loud sound. It just ruined a lot of things for everybody.” Claudia Calderon also came to the stadium to show her support. Born and raised in Los Angeles, Calderon said when she became a mother, she decided to move to El Paso to be near her family— and to feel safer. Now she feels afraid. There is “the fear that we thought we had left behind when we moved away from Los Angeles,” said Calderon, 36. “You know, you’re always watching your back in L.A., going from just to your car or whatever. There’s day-to-day violence there that you don’t see here. And all of a sudden, it felt like this bubble that we were living in bursted with this, with the violence.” Because she and her children are Hispanic-American, this particular white-supremacist shooting made a “huge difference,” to her. “I think that it instills a fear of being who you are.” She added that since the shooting happened, when she goes to the grocery store, she leaves her children at home — for now. Two days after the memorial service, many more El Pasoans gathered outside an overflowing church to show another survivor they were his new family. After 63-year-old Margie Reckard was murdered in Walmart, her husband Antonio Basco told the funeral home that he had no family in El Paso. He asked if he could open the funeral to the public. They had to move it to a larger church, because the response was so great. More than 900 flower arrangements and thousands of sympathy cards arrived from Texas, around the country and all over the world. People packed the church, and filed back outside after expressing their condolences, so others could enter the church. “We just had to come and show our respect for his family, and to show him how great El Paso is,” said Dolores Luna, 77, lifelong resident of the city. “We’re going to get through this, one way or another. And we’re just so sorry of this tragedy that happened. In our hearts, deeply in our hearts, we are with him all the way.” Luna, who was there with her family, said they often shopped at the Walmart where the shooting happened. “I just couldn’t believe it. Walmart is our number-one store for my children, grandchildren and great grandchildren. And I was just stunned. What if we would have been in one of the stores like that?” she told me. “My heart breaks.” She was outside the church with hundreds of other people to witness the arrival of Basco, who runs an El Paso mobile car wash. In the nearly 100-degree heat, hundreds upon hundreds stood patiently in line for hours, many holding colorful umbrellas to block the sunshine. “In our hearts, deeply in our hearts, we are with him all the way,” she said before walking up the church steps to greet Basco, who was surrounded by strangers hugging him. Basco, tears in his eyes, said he could not believe the response from the public to the death of his “angel.” After walking back down the crowded steps, Luna told reporters what she told the widower. “You will always remember this, especially for your wife,” she said. “We will never forget you. This is your home, and it is El Paso strong for you and your family.” Dan and Daisy Ramirez took their three children to the memorial for the 22 people killed 10 days earlier at an El Paso Walmart. The family quietly walked along the block-long memorial outside Walmart made up of candles, crosses, balloons, signs, stuffed animals and wooden crosses. Daisy Ramirez, who works at an El Paso Walmart at a different location, said she both dreaded visiting the informal memorial outside the Walmart, and felt compelled to come. “I just had to. I needed to come over here,” she said, standing at the edge of the memorial at the Cielo Vista Mall August 13. “I put myself in that cashier’s position, like what I would have done. I don’t know. I just needed to get it over with, and kind of relieve myself.” One of the Walmart cashiers was hit by a bullet, but survived. Twenty-two people were shot and killed August 3 by a 21-year-old man, a white supremacist determined to kill Hispanics in a hate crime. More than 24 people were injured. Hundreds of people continue to stop by the memorial, which looked like so many other cities’ mass shooting memorials. This one included signs of support from places of other shootings such as Dayton, Ohio, where nine people were killed and several people injured the day after the El Paso murders; from Gilroy, California, where three people were killed and 13 injured at a garlic festival in July; and Tucson, Arizona, where in 2011 six people were killed and 13 injured including United States Congresswoman Gabrielle “Gabby” Giffords. The El Paso couple said they have many friends and family — from both El Paso and Juarez — who regularly shop at the Ciela Vista Mall Walmart, referred to by locals as “The Mexican Walmart” because it is so close to the border and regularly draws many Mexican shoppers. The Saturday morning of the shooting, the store offered free or discounted back-to-school supplies including backpacks, so the place was filled with children, parents and grandparents. The Ramirezes believed it was important to bring their children, 4, 7 and 10, to the memorial. “It’s sad. We brought our kids so they could see that anything can happen,” Daisy Ramirez said. “They can learn from it and be aware of it.” Her husband agreed. “We don’t want to put it in our child’s mind, but we also have to be, you know, this is reality. I mean, life offers a lot of beautiful things,” Dan Ramirez said, “but there’s also things that we have to be aware of. And you just never know when anything can happen. You gotta be strong.” Like so many people whose communities have experienced mass or other kinds of shootings, Dan Ramirez said he found the incident difficult to comprehend. “We never thought it would happen. This community has been a very united place, very calm place, safe place,” said Dan Ramirez, born and raised in El Paso. “And, you know, for something like this, it’s just crazy and unbelievable for us.” They said that, as Hispanics, the shooting makes them wary. “With us, we’re more like on the lookout because we have the kids,” said Daisy Ramirez, who was born in El Paso but spent much of her childhood in Juarez. “So we’re constantly, like, looking back and forward.” She added she and other Walmart employees are on edge. “That next day, I had to go to work at 7:30 in the morning. And I was just really nervous [getting] from home to work,” she said. “Every person that goes in, we’re just looking after each other, you know. We’re on the lookout for anything, anything that might be suspicious.” The couple posed for a picture, deciding it was safer not to have their children photographed alongside them. Dan Ramirez picked up their 4-year-old son, and the family moved back toward the memorial. They joined dozens of others who were walking silently, some with tears rolling down their cheeks, many leaning on each other, past the keepsakes of memorializing. “It’s gonna be hard to get over all this,” Daisy Ramirez said. Not even two days after the 2015 shooting that killed nine worshipers in the African Methodist Episcopalian church in Charleston, South Carolina, some victims’ family members publicly forgave the racist shooter. At the court bond hearing of the gunman less than 48 hours after he murdered their loved ones, several relatives of those slain amazed the American public by expressing forgiveness for the young white man who killed the African Americans at the AME Church. He was hoping to reignite the race wars, he told police. Instead, he received the survivors’ absolution. “I forgive you,” said Nadine Collier, whose mother Ethel Lance, 70, was killed in the church. “And have mercy on your soul.” Collier was not alone. Several other AME church members expressed anger and deep sadness because of their losses, but also forgiveness. Polly Sheppard was not at the bond hearing. Though she had been in the church and survived the June 17, 2015, shooting, she did not want to speak publicly during the initial months. “I kept quiet because I wanted to go to those funerals, and [the media] didn’t know my face. I would be able to go without disrupting the funerals,” she said. It was several months before she spoke publicly about the violent ordeal. “I wanted to give the families time to grieve and everything before I started talking.” Today she has become one of the informal spokespersons for the survivors, and her message is often about the power of forgiveness. Forgiveness “relieves all the pressure off of you,” Sheppard said. “You’re at peace. It’s an inward peace.” Since the shooting, Sheppard has found herself in an unfamiliar position. “I keep saying it’s a new job, to talk,” said Sheppard who was 70 the night of the shooting. A retired nurse, her natural inclination had long been to shy away from the spotlight. Nearly four years after the shooting, Sheppard sat in her modest Summerville home, a large painting of President Barack and First Lady Michelle Obama on the wall. “I like to talk about forgiveness,” she said. “We forgave him, and I didn’t want the death penalty for him, either. I wanted him to be able to repent and turn his life around.” Summerville is a Charleston suburb, approximately 25 miles from downtown. Sheppard often travels to meet with other shooting-incident survivors. She recalled one man who argued with her about forgiveness. She was meeting with survivors of the 2018 Tree of Life Synagogue hate-crime shooting in Pittsburgh. An anti-semitic killed 11 people and injured seven during Shabbat services on October 27, 2018. One synagogue survivor told Sheppard he did not think he would ever be able to forgive the man who took so many lives that morning. “Well, you have to live with that. It’s a problem. If you forgive him, you can go on with your life. It takes time, and so it's not done right away,” she told him. In addition to her faith, which she admits was temporarily shaken that violent night in the AME church where she worshipped for nearly four decades, she is also a great believer in survivors seeking professional help. “They need counseling, they really need counseling,” she said, then turning to advice. “And, stay in prayer.” For her, though, forgiveness has been the key as both a survivor and a believer. “The forgiveness part, I think it helped,” she said. “People will call me, and tell me how glad [they were] to hear me, and how good they felt after I left.” The gunman in the AME church told Sheppard, “I’m going to leave you to tell the story,” she recounted, explaining why she was not shot. She said she is doing just that, but not by telling his story the way he had hoped. “That’s why I say divine intervention,” she said, indicating she was doing God’s work. “I’m not telling the story about him. I’m telling the story on forgiveness. And how God will lead you in the right direction if you listen.” For one survivor whose son was killed on the streets of greater Charleston, she is not there yet. “A lot of people, they come up with, ‘You should forgive him,’” said Tisa Whack, whose son Tyrell Miles, 23, was shot by a young man who lived nearby. The man, who is serving time in prison, never expressed regret for shooting her son and one of his friends, which makes it difficult for Whack to feel forgiveness. “I tell people I’m not there yet, and I’m not gonna lie to anybody. I hate this guy to a core.” Sitting in her office during her lunch hour, surrounded by photographs of her son, Whack referred to members of the AME church. “A lot of people use the example of the Mother Emanuel, when they talk about how they forgave and it was even less than 24 hours. And I respect them for that,” said Whack, whose son Ty was her only child. She and another mom grieving her own dead son started the nonprofit We Are Their Voices, to help other young men in the community. She said her son’s murder made her question her faith. Though she regularly attends church again, she is not in a place to forgive. “I still struggle with it,” Whack said frankly. A survivor of a different shooting does believe forgiveness helped him deal with the ripple effects of losing his father to gun violence. Pardeep Kaleka’s father and five others died in the 2012 shooting at the Sikh Temple of Wisconsin in Oak Creek, Wisconsin, and four others were wounded by the neo-Nazi who entered the gurwara, or temple, on August 5, 2012. Kaleka’s father, Satwant Singh Kaleka, 65, was president of the suburban Milwaukee gurwara. Kaleka found his way to forgiveness partly through his unexpected friendship with Arno Michaelis, a former neo-Nazi and former member of the violent, white supremacists group the Hammerskins. The Sikh Temple killer also belonged to that skinhead group, whose members are often in racist rock bands. A reformed Michaelis reached out to Kaleka after the shooting, offering his support. Eventually he and Kaleka wrote the book “The Gift of Our Wounds.” Kaleka said their connection created an atmosphere of forgiveness of the man who killed his father and other worshipers. The book focuses on learning about different cultures to bring understanding and forgiveness. After the temple shooting, Kaleka went to graduate school to become a counselor. He counsels people to forgive, when they are ready. “I would put the possibility in their hearts that, you know, forgiveness is a journey that they might want to take,” said Kaleka, sitting in his counseling office after a workout. He added that he would not suggest it too close to the date of their trauma. “What we get to is a place where I [suggest they] look back at their pain and they’re going to, you know, perhaps have this transformational approach to life.” Kaleka said that through forgiveness and acceptance of his vulnerability, he has learned to live in the moment and appreciate the life he was given. “In just the weirdest way, I’m much more happy,” he said. “And I don’t think that would have happened if the shooting wouldn’t have happened.” Kaleka recently took a new job, a move that seemed natural, given his path. In June 2019, Kaleka was named executive director of the Interfaith Conference of Greater Milwaukee, a nonprofit of faith leaders dedicated to building dialogue and relationships to counter hate and fear, and to fight for social equality. “When we talk about forgiveness and we talk about acts of kindness, we talk about, you know, who we are, who we’re meant to be,” said Kaleka, a father of four. “And I think those journeys are the ones that are the most worth taking.”  Pardeep Kaleka Pardeep Kaleka Hypervigilance often accompanies post traumatic stress disorder of gun violence survivors. Someone shot in a movie theater may choose to watch movies on television at home. Someone whose child was killed in school may be wary of sending their other kids back to school, whether or not it’s the same facility. For some survivors, time eases the hypervigilance. For others, being afraid never completely fades. And still, many refuse to let the fear run their lives. In June 2018, Pardeep Kaleka, whose father died in a racist act of terror six years earlier, was still feeling hypervigilant, especially in crowded spaces. “If I’m at a coffee shop, I’m a little bit hypervigilant. If I’m in a public place, I don’t really feel safe,” he said, sipping a bubbly water as he sat on an outdoor patio of a Milwaukee coffee shop in June 2018. Kaleka’s father, Satwant Singh Kaleka, was president of the Sikh Temple of Wisconsin in a Milwaukee, Wisconsin, suburb. On August 5, 2012, Satwant Kaleka and five others were shot to death by a racist neo-Nazi, and four people were injured. A former police officer, Kaleka said it took will power and a leap of faith to let his kids walk from his car into school after the temple attack. The Sandy Hook shooting happened the same year as the Sikh Temple shooting — just four months later. “If I’m in a school, and I’m dropping my kids off and, you know, this was at the time that Newtown happened, that thing happened, and you’re just seeing it all over the place,” he said. “And the threat is real. And that takes you processing.” And during an interview a year later, Kaleka, who after the shooting went back to school to become a counselor, said he no longer felt fear in the same way. “I think the hypervigilance has kind of left,” he said, sitting at a large table inside his counseling office in June 2019. “And I’ve been able to process through it. And it was really like saying, ‘Okay. I existentially embrace the vulnerability of life.’” He says that outlook often leads to living in the current moment, while still hoping for a future. “I have things that I need, I want, to live for. I want to watch my kids grow, I want to see them get married, I want to see my grandchildren. I want to see life,” he said. “But at the same time it’s just, I’m not going to be scared. I’m not. Either you can be scared of life, either you can be scared of the next shooting happening. Or you can, you know, really do something about it, and try to prevent people from getting hurt. And also not be scared of it.” For Polly Sheppard, who survived the 2015 African Methodist Episcopal Church racist shooting in Charleston, South Carolina, fear of returning to her church, often referred to as Mother Emanuel, does not mean she is afraid to leave the house. “The atmosphere is different,” she said of the church where her best friend Myra Thompson and eight others, all African Americans, were murdered by a white man who later told police he had hoped to reignite the race wars. “I get a kind of eerie feeling when I'm in there.” Since the shooting, Sheppard worships at another AME church in Charleston. Occasionally, she will visit old friends at Mother Emanuel, but only during the day. On June 17, 2015, a white supremacist entered the AME church basement where Sheppard and 11 other worshippers were attending an evening bible study group. They welcomed the stranger into their midst. The gunman sat with the group for nearly an hour, and when most of them were praying with their eyes shut, he pulled a gun out of his fanny pack, and began shooting. Nine people died, including senior pastor and state senator Clementa C. Pinckney, and four other church ministers. The gunman did not shoot Sheppard, telling her he wanted her to live to tell the story. In addition to the fear the gunman hoped to bring, a faceless group also applied hatred and pressure toward Sheppard after the shooting. “I got a message on my computer from the Ku Klux Clan one day after I’d been on TV,” she said. “Telling me to stay off TV. And, ‘We know where you live.’” This was soon after Sheppard’s story aired on NBC’s Nightly News with Lester Holt. He interviewed Sheppard and survivor Felicia Sanders approximately three months after the shooting. Sheppard said she called the police about the message, but they did not track down the intimidating email sender. While the message frightened her initially, in the long run it mostly made her angry. “I'm not actually that afraid of them. I just hate for them to even be able to tell me anything,” she said, frustrated that strangers with such a dark message could get onto her email. “But it didn’t, it didn't scare me to where I wouldn't go out or nothing. I was angry. But that's it.” She paused and then smiled mischievously. “[If] I could catch him, I would ring his neck,” she said. Sheppard laughed in spite of the seriousness of the situation. She did admit that, since the shooting, she’s not as active as she once was. “Well, I’ve kind of slowed down,” she said, again uttering a quiet but deep laugh of someone who has known great joy over the years. “I'm not interested in going out too much. 'Cause it’s, — I realize I don't know everybody. But I can't be afraid all the time either. But I don't go out too often.” She said that since the shooting her life has changed in other ways, too. Now strangers recognize her, and people known and unknown to her want to speak with her. “Life is altogether different. And everybody wants you to talk. And everybody think, they think I got something special. Some people that they have seen all I saw, they wouldn't be quite as stable,” she said, adding that more than a year of counseling helped her. “I don't have anything special. I say, the Lord does it. And he's available to everybody.” Sheppard, who said because of the shooting she has met civil rights activist John Lewis, South African former Archbishop Desmond Tutu, President Barack Obama and First Lady Michelle Obama, feels privileged to be one of the informal spokespersons for the AME worshipers. Still, when people want to touch her, she takes it with a grain of salt. “They say, ‘Oh I just want to touch you, I just want to’ — everywhere I go somebody want, they want to hug you,” she said and paused. “I think it's just amazing. They're just amazed that I'm still alive and my mind is straight. Yeah.” And here came that laugh again. Fourth of July: Parades, peppermint-candy ice cream, and fireworks. What could be more fun than these Independence Day traditions? If you are a survivor of a shooting, however, this holiday may not feel like a time to celebrate. Exploding fireworks, or the crush of a public event like a holiday parade, can trouble survivors of gun shootings — even if the bullets never reached them. Mindy Scott is a waitress who survived the Route 91 Harvest music festival shooting in Las Vegas October 1, 2017, and drove many of the wounded to the hospital. Later she found solace in her closet when fireworks exploded on the next New Year’s and again on the Fourth of July. She, her 21-year-old daughter, and her two rescue dogs made it through together. “I lived right next to the Strip. So on New Year's Eve, I got to hear all the fireworks from the Strip,” she said, adding her family moved to a different house after the shooting to try to get away from the horrendous memories. “I hid in my closet with the headphones on,” Scott said about the Las Vegas New Year’s fireworks that occur every year. But this was not just any year. It was only three months after the shooting that killed 58 people and left more than 400 wounded. “I sat with my dogs, my pit bulls, as they snuggled me,” she said. “And that’s how we did it through the night. And when it was done, we went to bed. It was just getting over that little hump. The next one was Fourth of July, of course. “And it’s not the big booms. It’s the little ones, the popping ones that affected me. Or you just sit outside and somebody would, like, a month after the Fourth of July, people were still letting off fireworks. And that would get to me.” It is not only fireworks that can spin survivors into a panicky flashback. “It could be a vehicle backfiring, or a door slamming, or a car driving over a manhole cover that can send people over the edge,” Scott said, sitting in her new backyard a few miles from the Las Vegas Strip. It is quieter than in her former house. “Or we would hear too many sirens coming down the street. And it was almost like my heart felt like it was just beating out of my chest. ’Cause my anxiety would just get so high from it. I mean, now I don’t hear it.” Pat Maisch, who survived the January 8, 2011, Tucson shooting, was credited for grabbing the gunman’s magazine before he could reload. Thirteen people were wounded, including U.S. Congresswoman Gabrielle “Gabby” Giffords, the target of the attempted assassination. Six people were killed, including 9-year-old Christina-Taylor Green. Maish said she still can be triggered by being in the vicinity of the shooting. “I would drive by there, and after I get over to Ina [Road] and First [Avenue] my hands, I just start flexing my hands because they felt really tense,” Maisch said. “One day I stopped at the light, and I found myself clutching the steering wheel tightly. And so, it does have a long-lasting effect on your inner being.” Like Scott, Maisch said even the most common sounds can cause flashbacks. “It doesn’t have to be a gunshot that takes you back. Right over Swan and Sunrise [roads], even though I know this big grate is in the street. If I am not paying attention and I hit that grate with my truck, just that ‘ka-kow’ will take you back,” she said. “You know, it’s just any kind of sudden noise.” She added that even if a loud noise is expected, it can still have a negative impact. Approximately a year and a half after the Tucson shooting, Maisch went to a funeral during which there was a 21-gun salute. “Even though I knew it was going to happen,” she said, “a 21-gun salute, I don't know how long that takes, but it shakes you to the core.” That is mostly because she had experienced the 33 rounds being shot in approximately 20 seconds in Tucson in 2011. Like many gun violence survivors, Maisch has become hyper-vigilant. “When I go to airports or crowded places, unintentionally or unconsciously, you sort of look around and see what’s happening and what you might do if something did happen. So that becomes part of your life, where you don’t have the freedom not to think about,” Maisch said. She slipped into the third person as survivors sometimes do, perhaps as a self-protective mechanism. “You look for that tornado shelter when you’re in St. Louis, you know, or Atlanta. You think, ‘What would I do if something happened?’” For one survivor of the June 12, 2016, Pulse nightclub mass shooting in Orlando, Florida, going out at night has become a challenge. Ricardo Negron-Almodovar, a Puerto Rican lawyer who moved to Orlando less than a year before the shooting, was not injured that night. In fact, he ran outside when the shooting began, and did not realize it was a major incident until he woke up the next morning. Still, it changed his life. “It comes, like, it varies,” said Negron-Almodovar a legal services coordinator at Latino Justice, an Orlando nonprofit. “Like if I go out on a Saturday night to a Latin [music] place. That’s when it’s mostly there. But I still, like, I want to go out and enjoy and have a good time. I love going out to dance and stuff. So it’s kind of like a mess.” The shooting still impacts his emotions. “Sometimes I find myself getting very angry,” Negron-Almodovar said. “And I know it’s related to that, to that feeling of impotence almost that you had that day.” Many gun violence survivors share these feelings. Too many others, thousands — including children who were at school or simply walking in their neighborhoods — can no longer experience any kind of feelings, or participate in Fourth of July activities. They do not get to decide if they want to go to the parade, spread a blanket out to watch the heavens light up above them, or take a peaceful walk in the woods. They are dead. |

AuthorMary Tolan is a fiction writer and journalist. Her first published book Mars Hill Murder, a mystery set in Flagstaff, will be published by The Wild Rose Press in autumn of 2023. Archives

May 2023

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed