Sunset dedication of the Las Vegas Community Healing Garden. Sunset dedication of the Las Vegas Community Healing Garden. Fifty-eight doves were released soon after sunrise. They flew high over the anniversary crowd, circling overhead, once, twice, white wings flapping, before disappearing into the sky. Each bird was tagged with the name of a person murdered in Las Vegas a year earlier at the Route 91 Harvest country music festival shooting Oct. 1, 2017. It was the worst United States mass shooting in recorded history. Anniversaries bring celebration, memories or milestones. In our world of escalating gun violence, however, the anniversaries — while they may bring survivors together in healing — recall a day of fear, shock and devastating losses. At the first anniversary of the Route 91 Harvest massacre, which killed 58 people and injured more than 500, people spent the day at memorials, a dedication, a survivors-only country music concert, and reconnecting with members of the “family” they inherited that deadly night on the Las Vegas strip. The shooting happened at an open-air venue owned by MGM Resorts International, which also owns the Mandalay Bay Resort and Casino. It was from that hotel overlooking the festival grounds where the shooter perched and took aim at his innocent victims 32 stories below. At the sunrise service Oct. 1, 2018, right before the flock of doves took wing, the crowd heard from Minda Smith, whose sister was killed at the music festival. Neysa Davis Tonks was a single mother of three, out for a night of music when her life ended. “Our love must motivate us to move forward,” Smith told the crowd gathered at the county amphitheater. “We have the right to feel angry and sad. Embrace those emotions, but don’t let them control you.” She spoke of her sister, and her family’s loss as her — and her sister’s — parents’ wiped away tears. “I refuse to let it take one more thing from me.” At the sunrise service and other memorials, people wore T-shirts that read Vegas Strong, or Country Strong, or Strong 58, or Country Folks Will Survive. Tattoos were commonplace, many of them with the inked words Vegas Strong rising from the Vegas skyline. In the heavy presence of law enforcement officers at the sunrise service, pipes and drums played “Amazing Grace,” followed by a choir singing “When You Walk Through a Storm,” “You’ll Never Walk Alone,” and “America, the Beautiful.” People cried, embraced and spoke of sadness, encouragement and love. A woman police officer hugged a young man and woman holding a baby. A middle-aged couple in jeans, cowboy boots and hats, held hands, looking like they would never let go. Some survivors braved speaking to reporters as they fought back tears, but others requested privacy to be alone with their thoughts or with the friends who had experienced the deadly rampage alongside them. Several survivors appeared to find solace while stroking an emotional-support St. Bernard. A woman buried her wet face in the dog’s thick coat. One cop talked quietly to a man. “You only have one life to live,” the officer said. “You have to find your path.” They nodded together. Gov. Brian Sandoval spoke to the crowd. “We will never fully recover from that fateful night, nor should we,” he said. “But from that night of Nevada infamy came one of our proudest moments. We become one people, one community, one family. We cried. We grieved. And we resolved to become Vegas Strong.” The theme of angels was everywhere in the city. In shops, restaurants, and hotels, figures of angels were displayed in memory of those slain, and Vegas Strong signs were taped onto storefront windows. In the evening, hundreds of people gathered at the Healing Garden, built just days after the shooting. It is located on what had been a vacant downtown lot. People placed 58 roses at the new memorial wall. Las Vegas Mayor Carolyn Goodman recalled how the city was overrun with blood donors that tragic week. People needed something to do with their desire to help. Within hours, the idea for the healing garden was born. Created by volunteers, it opened to the public five days after the shooting. “Seize the day and make your life. You’re blessed to be alive,” Goodman said. “We saw the sign in the sky.” Mid-ceremony, a strange and beautiful cloud shadow created a funnel-shaped beam of light, as if signaling joy or compassion to those who had gathered throughout Las Vegas to remember. Jay Pleggenkuhle, garden project director, spoke. “We planted a garden not thinking of trees and flowers, but of love, hope and passion,” he said. “Take good care of each other, respect each other, love each other. We’ve pushed back with a very deliberate act of compassion.” Thousands of people gathered on the Las Vegas Strip at 10 p.m. to witness the dimming of the marquees in honor of those killed and wounded at the music festival shooting. People stood close to one another, packing foot bridges over Las Vegas Boulevard, waiting. Nearby, dozens of survivors linked arms and created a human chain around the still-fenced-off shooting site. A year after the shooting ripped into the lives of hundreds of country music lovers, the marquees began to dim just after 10 p.m., as did the famous Welcome to Las Vegas neon sign. At 10:05 p.m., the Strip went dark.

1 Comment

When people are killed or injured by gun violence, a ripple effect moves beyond the individuals who were shot. It is not just those who were killed, or the survivors and witnesses to shootings who are affected. Also affected by shootings are the relatives, friends, and even people they do not know at the time of the shooting.

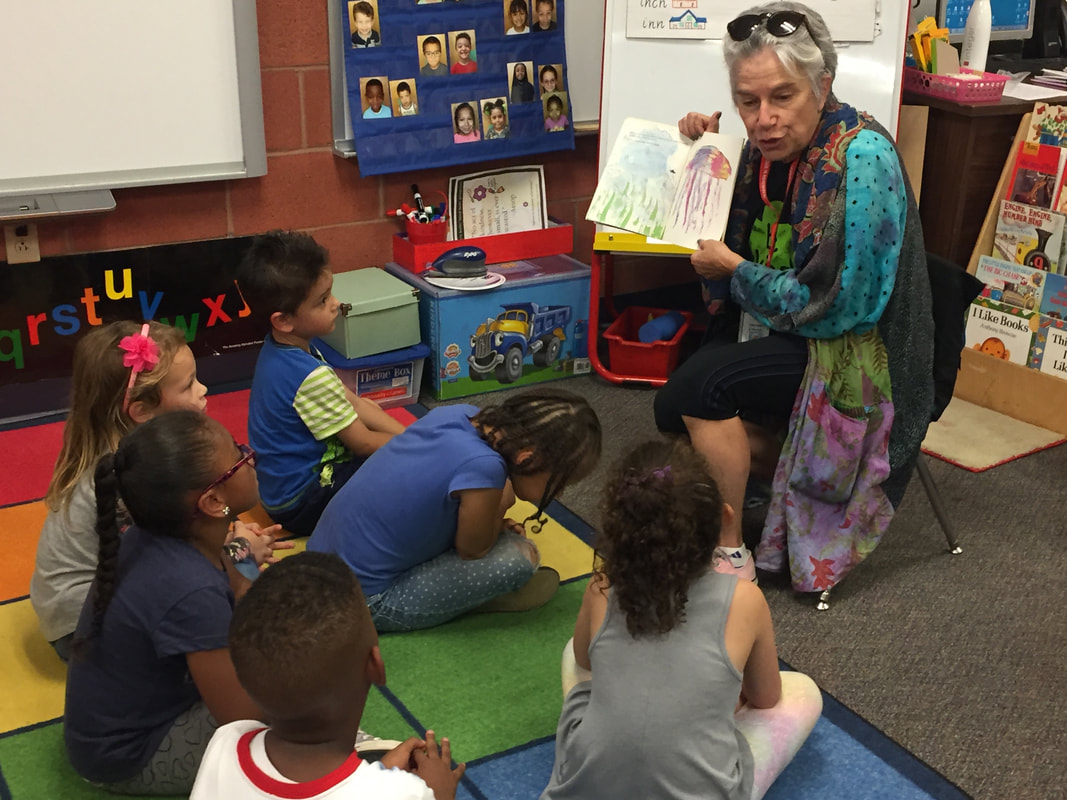

Ron Barber was District Director for U.S. Representative Gabrielle “Gabby” Giffords, who represented southern Arizona, including Tucson. Barber was shot twice — once in the face and once in the leg — during the attempted assassination of Giffords. Giffords was outside a Safeway store in Northwest Tucson at her “Congress on the Corner” event meant to bring her in contact with constituents who had comments or complaints. The shooter was a mentally ill young man who had become obsessed with Giffords. She survived, but retained serious brain damage from the bullet to her head. She struggles to put her thoughts into words, and is partially paralyzed. During Barber’s long recovery, which included dealing with physical and emotional pain and PTSD, his wife Nancy quit work as a doula to take care of him full-time. They said it was a rough road, and even their grandchildren were affected. “My oldest granddaughter, she’s 14 now. She is still dealing with it. Whenever a family member is missing in action, if you will, or doesn’t came back on time, she gets very, very anxious,” Ron Barber said about the youngster who was 7 at the time of the shooting. “For [her] it’s been a terrible thing ever since.” Nancy Barber added that they turned to a helpful technology, one that might seem invasive but is essential to the health of their granddaughter. “On our phones we have an app called 360. And we, the whole family, all of us, the other grandparents” have the app, Nancy Barber said. “And you can go on that app and know exactly where everybody is. Pull it up and you can even see the buildings they’re in. So that was crucial to her anxiety.” The Barbers said their 14-year-old granddaughter and 17-year-old grandson still struggle with anxiety as a result of the shooting. Their grandson was the same age as Christina-Taylor Green, who died, their birthdays just five days apart. Suzi Hileman was Christina-Taylor’s friend and neighbor, and was holding her hand when they were shot. Hileman still grieves the loss of her young friend, and not long after the murders, she contemplated getting involved in the gun-reform activist movement. That’s when she learned how much the shooting had devastated her husband and grown daughter. Her husband Bill had asked her to hold off on putting herself into public spaces. “I paid no attention to it because I was pretty excited about myself,” Suzi said, imagining being in the spotlight, helping the cause. “And then my daughter Jenny called.” Jenny said she and her father did not want Suzi to become active in publicly speaking out against gun violence. Then Suzi asked her daughter, “Honey, what are the chances?” That’s when her daughter exploded on the phone. “Don’t, God damn it! Don’t you ever say, ‘What are the chances of you getting shot?’ How can you say that? What would I do if you got shot again? I can’t go through this again.” Her husband Bill Hileman explained. “It wasn’t just the fact of what happened. But there was a visceral side to it for Jenny and me, seeing her laying unconscious in that emergency room, the ICU. Tubes coming out everywhere. Filleted, you know, her torso opened up just like a fillet,” described Bill Hileman, fighting to contain his emotions. “And she looked so little and beat up. She was so bruised everywhere. She had all this internal bleeding and she was purple all over the place.” Since then, Hileman has focused her post-shooting energy on working with elementary school children in memory of Christina. Mentoring 6-year-olds in gardening and reading, she considers it her second career. For Bill, his life’s purpose has changed, too. After decades in a high-profile career, he had retired years before the shooting, choosing a quieter life with more time for the family. “I’m very private now, and happily so. But this pushed that process along,” he said of his new perspective. “I just want to protect the family. It’s my overriding sense of things. I just want to protect Suzi.” He said he was happy when Suzi turned her attention to young school children instead of the gun-reform movement. “While we are supportive of it,” he said of those carrying the gun-reform torch, “I just didn’t want the love of my life to be front line on that. Selfish on our part. But my overriding reaction to the entire thing was to protect my wife.” He said after nearly eight years since the shooting he’s not necessarily afraid at home, but careful. “I don’t like anyone coming to the door without checking to see if there’s a bulge at their hip,” he said. And neither Suzi nor Bill is completely comfortable in public, and do not like to sit with their backs to the door. And if there is a gun present, the psychological alarms go off. “We’ve left restaurants and other such things when people come in carrying,” Bill Hileman said. “I don’t want to be around guns. I just don’t want to be around the randomness of human behavior armed with the power over life or death. I just think it’s a bad combination.”  Mindy Scott's Vegas Strong tattoo. Mindy Scott's Vegas Strong tattoo. It seems hard to believe that within an 11-day period last fall, two mass shootings occurred in the United States. It should not be. In fact, many more people died in U.S. shootings during that time, though not generating the same media attention as the shootings in the Pittsburgh synagogue and the southern California bar. Traveling the country since June 2018 to interview survivors of gun violence — from mass shootings, random shootings, inner-city violence by guns, and more — I have come to see this as almost ordinary. In fact, it is. According to the Gun Violence Archive, a not-for-profit group that offers online access to gun-violence statistics, the Thousand Oaks Borderline Bar & Grill shooting was the 307th mass shooting — taking place on the 311th day of 2018. That means an average of one deadly mass shooting happened every day last year. As I transcribe the interviews I’ve gathered, a dark, sickening realization hits me: This is how the new normal feels. It is a tragedy that we have thousands of witnesses who can tell us exactly how a shooting feels, and about the physical and psychological pain that continues for years. And when I read the newspaper accounts or hear the radio and TV reports about the most recent shootings, I feel I almost know the latest survivors. I’ve not yet met anyone who was at the Thousand Oaks, California, bar Nov. 7, when the murderer stepped inside with the intent to kill at “college country night.” But I have met people who attended the Route 91 Harvest country western music festival in Las Vegas Oct. 1, 2017, when 59 people were shot to death and more than 500 were injured. One survivor of this shooting, Mindy Scott, wept as she told me her story. Scott had gone to the music festival with her 21-year-old daughter — the first country western concert they had attended together since her daughter became an adult. “I didn’t sleep for two days. And she stayed in my arms for two weeks,” recalled Scott, a waitress. She and her daughter still flinch at loud noises, a common trigger for gun-violence survivors. Fireworks can be the worst triggers, even if the brain tries to assure the survivor all is well. “On the Fourth of July,” she said, “me and her sat in my closet with headphones on, watching movies, with our dogs at our side. The dogs get us through this, to this day.” Scott and her husband, an Uber driver, carried dozens of shooting victims from the shooting site to the hospital in their two vehicles for several hours following the shooting. Not long before the one-year anniversary of the shooting, the family moved into a different rental house, because from the first one she could see the Las Vegas Strip where the shooting occurred — that was just too painful, Scott said. I’ve not met the members of Pittsburgh’s Tree of Life synagogue, where shots broke out October 27, 2018, leaving 11 dead and six injured Oct. 27. I have, however, interviewed those who survived another hate-crime shooting, at the Sikh Temple in Wisconsin. I spoke with survivor Satpal Kaleka, whose husband Satwant Singh Kaleka was the spiritual leader of the temple, and who was shot to death as he struggled with the gunman in 2012. Five other worshipers died, too. Satpal Kaleka is deeply spiritual, and believes “all is in god’s hands.” Still, she and others who hid from the gunman that Sunday, today find themselves imagining exit routes during the weekly service. Several people were injured, including a police officer who was shot 15 times, and survived. I have not yet interviewed the Parkland students who witnessed the shooting at the Marjory Stoneman Douglas High School on Valentine’s Day, 2018, leaving 17 dead and as many injured. Since then, many of those who survived that shooting have become activists in the gun-reform movement. Finding a new path is not unusual for people who survive shootings. After time, many survivors and those connected to shootings find a new direction for their lives. For those of us who have not been disabled by gunfire, witnessed a fatal shooting, or had our loved ones murdered, this may seem a distant reality. It may seem surreal as we watch the news in the safety of our living rooms, or follow along on our smart phones. One trauma surgeon turned policy-maker, however, says we ought not to fool ourselves. Dr. Randall Friese was just coming off a 24-hour hospital shift when the calls came in about the Tucson shooting. He performed surgery on 9-year-old Christina-Taylor Green, but was unable to save her. He then turned his attention to U.S. Rep. Gabrielle Giffords, who survived a shot in the head in an assassination attempt Jan. 8, 2011. She has brain damage and is partially paralyzed, and has become active in gun reform. After that very long day of blood, death and surgeries, Friese was changed. Over time, he decided he might do more as a legislator than as merely a trauma surgeon. He ran for office, and now is a state representative in the Arizona House, pushing for changes in gun laws. None of those bills he has introduced in his red state have made it to a hearing, however, even one that simply requested the creation of a study committee on gun violence. Still, he believes in pushing for reform. “Just because it’s never touched you or your immediate family, it may have touched a neighbor, and you’re not aware of it. Or a child that goes to school with your child,” said Friese, who divides his time as surgeon and legislator. “So I’m trying to get people to understand that it’s closer to you than you think,” said Friese, who was re-elected Nov. 6, 2018. “And if we don’t do something to change that trajectory, it’s going to eventually touch you, or someone very close to you.” The U.S. gun violence epidemic leaves thousands dead, injured, and forever changed

When people are killed or injured by gun violence, a ripple effect moves beyond the individuals who were shot. It is not just those who were killed, or the survivors and witnesses to shootings who feel the impact. Also affected by shootings are the relatives, friends, and sometimes even people they did not know at the time of the shooting. Last year, more than 14,600 people were killed by guns in the United States. Another 28,000-plus were injured in approximately 57,000 incidents, including 340 mass shootings, according to the not-for-profit Gun Violence Archive, which provides statistics on gun-related violence. (These 2018 numbers do not include the 22,000 annual suicides.) In Tucson, Arizona, a survivor of the 2011 “Gabby Giffords shooting” says his granddaughter, who was not even at the deadly incident, still suffers from anxiety brought on by the shooting of her grandfather, Ron Barber. Also in Tucson, the wife of a man who tackled the gunman that sunny Saturday morning, said for two years she was very afraid every time she left the house. Sallie Badger absolutely “knew” a gunman would be waiting for her after she got into her car. She was not even at the shooting that claimed six lives and left 13 people injured, including her husband Bill Badger. A woman who was there, holding the hand of a 9-year-old girl who did not survive the shooting, has spent months and years recovering from her wounds from the three bullets that entered her body. Suzi Hileman is forever impacted by the trauma of losing her young friend. Only after she told her own family that she hoped to join activists fighting for gun reform, did she learn about the trauma her grown daughter had gone through during the long days her mom lay unconscious in the hospital. “It’s just the ripple effect of it,” said Hileman of gun violence. “How it touches everyone.” In suburban Milwaukee, a gunman came to a Sikh temple with the intent to kill. He murdered six people including Satwant Singh Kaleka, the temple’s president and spiritual leader, as many of the congregation hid in the pantry while gunshots exploded. Since then, Kaleka’s wife Satpal Kaleka has a difficult time concentrating on the Sunday service. She and others who were there imagine an exit route — while they would rather be concentrating on their spiritual lives. One of their sons, Pardeep Kaleka, changed his career after the shooting, becoming a trauma counselor focusing on men’s anger. He was driving his children to the temple when the shooting occurred. And a mom who took her 21-year-old daughter to a country music festival in Las Vegas that turned into the worst mass shooting in U.S. history to date, tells of eight months later when the two hid in her closet with headphones on and their dogs at their sides, trying to block out the sound of fireworks exploding. Neither Mindy Scott or her daughter was shot, but they suffer from PTSD and will never forget the shooting. My name is Mary Tolan, and I am a journalist and journalism professor. On sabbatical this year, I am reporting on the survivors of gun violence. I’ve interviewed people in Tucson, Milwaukee, Las Vegas, a random-shooting victim in Phoenix and a nursing student who witnessed her two professors being shot to death during her 2002 midterm exam at an Arizona university. I will travel to other states to continue my reporting. Disturbingly, there is no shortage of places to visit regarding these tragic, all-too-common events. I have never been at a shooting, and I hope I never am. But with the numbers of gun-related violence on the uptick in this country, I half expect that I will witness a shooting in my lifetime. I pray my children never will. Deaths by gun fire in the United States are among the highest in the world. In 2017, 12 people out of every 100,000 died in this country, compared to 0.2 deaths in Japan, 0.3 in the UK, 0.9 in Germany and 2.1 in Canada, according to the Journal of the American Medical Association. The study found that “just six countries in the world are responsible for more than half of all 250,000 gun deaths a year. The U.S. is among those six, together with Brazil, Mexico, Columbia, Venezuela and Guatemala.” Compared to 22 other high-income nations, the gun-related murder rate in the U.S. was 25 times higher in 2010, according to the American Journal of Medicine. What I’ve discovered on this path of reporting is the bravery, insightfulness, despair and hopefulness of the survivors I’ve met. People who were interviewed by the media for many hours immediately after the shootings, and who are still willing to open up — and often open up their homes — to yet another reporter. When a shooting happens, especially a mass shooting, journalists swoop in, often focusing on the victims who died or the actions of the perpetrator. These are important stories, of course. But too often those same journalists leave when the next big story breaks, and the tales of the survivors are forgotten. I’m not sure why I feel called upon to share the stories of these survivors. Simply, I do. Some survivors I’ve spoken with years after the shooting, others at the first anniversary or even earlier. Meeting with them has been inspiring, emotional, and deep. Being shot or having a family member killed or wounded by gunfire changes a person forever. What I’ve discovered is the ripple effect of these shootings. Many survivors mention this phenomenon. Like a stone tossed into a pond that creates rippling circles, a gun shot’s impact travels from the people hit, beyond those individuals and outward into the world. My blog, “The Ripple Effect, the Stories of Gun Violence Survivors,” will encourage survivors to express in their own words what they and their circle of friends and acquaintances have been through, and the impact on their lives months or years after the shootings. I thank all the survivors who have so generously shared their stories with me. I welcome others to join them as I travel the country, listening. |

AuthorMary Tolan is a fiction writer and journalist. Her first published book Mars Hill Murder, a mystery set in Flagstaff, will be published by The Wild Rose Press in autumn of 2023. Archives

May 2023

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed