Brenda Bell, UT Tower, Austin. Brenda Bell, UT Tower, Austin.

Once considered a beacon of inspiration, a call to tourists and natives alike to gaze upon Austin’s skyline, that all changed on August 1, 1966. On that summer day, a gunman with an intricate plan to kill as many people as possible shot hapless students, professors and civilians 28 stories below. At the end of the slaughter from the University of Texas Austin Tower, he had killed 14 people (including an unborn baby), and wounded more than 30 others. He was shot and killed in the tower after holding the campus hostage to his gunfire for more than an hour and a half. Since that day — one that whispered the beginning of mass shootings in the United States though none followed until decades later — for some people the tower carries them back to that terrifying incident every time they glance upwards. “Any time I look at the University of Texas Tower, I automatically look to make sure there’s nobody up there,” said Forrest Preece, who witnessed the shooting when he was a 20-year-old student. “Every time I see it, I relive that day.” Preece, 72, who worked in the advertising field in Austin for many years, said the shooting changed him. “I will say there hasn’t been a day in the last 53 years or whatever it is here that I haven’t thought about it,” said Preece, who said he has read everything he could find about the event, has talked with other people who were there that day, and has met with many survivors and relatives of the victims. Brenda Bell, a longtime journalist for the American Statesman and a 20-year-old student who witnessed the Tower shooting from a classroom window, agreed that Monday in 1966 changed the significance of the Tower for those who were there. “We never, we never, never, never look at the Tower without thinking about that. You know, it’s impossible,” said Bell, 73. “But for most people now, I don’t think it’s in their mind. I think it’s just, you know, the remnant population that’s left that was there. [For them], that will never be gone.” Neal Spelce reported from the scene that day for the radio station KTBC. He agreed on the significance of the Tower, which stands at 307 feet and was completed in 1937. At other shooting sites, he said, there may be a memorial to remember shooting victims, but those are not like the looming building seen from the university grounds and from neighborhoods across Austin, the state capital. “But here, the tower dominates everything. Everything,” Spelce said. “So it has maintained, that is one of the things I think that has kept the story out there, that equates to surviving — a surviving story.” Preece, who grew up in Austin, said as a child he considered the Tower inspiring. But that was ruined by the shooting. “As a lifelong Austin resident, I resent this fact,” Preece said. “My whole childhood, I was full of the expectation of one day being a UT student and enjoying my classes there. Before the incident, the tower was a symbol of hope and aspiration for me.” Preece said his mother told him years ago that after she gave birth to him, she reflected on the fact that he was born in the shadow of the UT Tower. “How ironic that the existence of that tower almost cost me my life 20 years later,” he said. Still, the tragic event also enhanced his gratitude for life. He recalled a bullet literally whizzing past his ear. “The randomness of the universe landed in my favor that day.” Preece said. “It’s…made me appreciate what I was given through sheer luck that day--a second chance to get out there and make something out of myself.” While thousands of people have died at the hands of mass shooters in the U.S. since 1966, at the time it seemed a one-off — an unimaginable and never-to-be repeated killing spree. When the Columbine High School shooting happened three decades later in 1999, killing 12 students, a teacher, and wounding more than 20 more people, that shooting became known in the collective consciousness as the first such event. But it was not. “There was no precedent for this,” recalled Bell of the Tower shooting. She went on to write about the shooting several times on its various decades’ anniversaries. “You know, we didn’t even have a movie. We hadn’t read the book. We didn’t get the memo. So there was no, there was nothing that we could compare this to except a movie that we hadn’t seen. So the shock and all was just universal that day.” The uniqueness at the time of the evil act was true for journalists, too. “There was no plan for coverage. Zero. Nothing like that had ever happened before,” recalled Spelce. “Now I’m sure newsrooms have their disaster plan — what to do, who to call, send the word.” Many heroes emerged on that hot August day in Austin. People pulled the injured off the mall area below the tower, risking their own lives. Journalists covered the event as bullets rained down. One student risked her life by lying on the sweltering concrete next to a pregnant woman — the first person shot, whose baby died from the wounds — just to talk until help arrived. It was a life-changer even for those who witnessed it from nearby, like Brenda Bell. “It was this seminal event,” Bell said. “And from the day it happened I was just consumed with, kind of curiosity — maybe morbid curiosity — about the whole thing. And about what other people were thinking, and how they were dealing with it.” Bell said watching the shooting from the window of an English class classroom influenced her choice of careers. “It did have a lot to do with me being a journalist,” she said. “I’d never seen suffering like that. I’d never seen someone die in front of me. I’d never seen people bleeding, you know. A pregnant woman lying in front of you. I’d never seen those things. And so I became, I wanted to know more about that. And so it kind of became a minor obsession, you know, through the years when I did become a journalist.” She took away something else, too. “I'm not brave,” she said, she realized when she stayed at the window, unable to move outside to help others during the gunfire, feeling like a coward. She remembered watching a student run out to help carry the wounded pregnant woman off the mall. “It was just so human, and so brave, you know. And so opposite of me,” she said. “He was like this super hero as far as I’m concerned.” Bell said she’s observed through the years how the ripple effect has impacted people differently. “What it felt like to me was a ripple. A ripple, ripple, ripple that never stopped,” Bell said. “There is a shore, a far shore, but it never reaches it. It just keeps going.” She referred to families that ended in divorce partly due to the impact of the shooting, people who swore off guns, and people who seemed unaffected. “I remember the father of one of the victims. He sold all his guns. He had guns. He sold them. He never wanted another gun in his house,” she said. But one wounded man had a different reaction. “He’d been shot,” she said. “And he seemed to go on as if nothing had happened. But other people, you know, there are some people in town who are obsessed with the Tower thing. And if you ever run into one at a dinner party, everyone leaves the room because the obsessive conversation starts.” Bell said the ripples have now moved on to the children and grandchildren of people who were there in 1966. A daughter of one of the police officers who shot the gunman that day became an Austin police officer. Bell believes the difference between a shooting and a bad accident is the intent, and the weapon. “The gun aspect of it,” she said, “I think it makes it different from something like a 30-car crash on the highway, or, you know, a tsunami. I think it makes it different because of the malice involved. You know, and the intention. It’s not an accident.” Ironically, or perhaps tellingly of the times, for years most people referred to the Tower shooting as “the accident.” That is, if they talked about it at all. For many people at the shooting — and the University of Texas itself — not talking about it seemed an attempt to make the whole tragedy go away. For years, there was never even a marker or even a historical note on campus about the shooting. Unlike the reaction to the 2017 Marjory Stoneman Douglas High School shooting in Parkland, Florida, that birthed the students’ political activism, the 1966 Tower shooting was nearly swept under the Texas rug. But not for the survivors. “I’m just trying to get rid of this ghost,” said Preece.

0 Comments

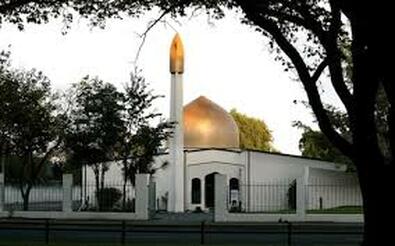

Last week, on March 15, a White nationalist gunman in New Zealand shot to death 50 people and injured approximately 40 more at two Christchurch mosques. He videotaped the shooting, live-streaming it on Facebook and Twitter. Before he began the massacre of Muslims at Friday night prayers, he sent out a racist, anti-immigrant manifesto to government officials and the media.

As people across the globe mourned with the families of those killed, and with the survivors, the New Zealand prime minister vowed to take action. Jacinda Ardern said the country’s lax gun laws needed to change. “They will change,” said the prime minister at a news conference. She added that her Cabinet planned to reassess the country’s policies on gun control immediately. According to media reports, compared to many countries, New Zealand has fewer restrictions on shotguns and rifles, while handguns are more tightly controlled. Yet the country, unlike the United States, has relatively few murders by gunfire each year, and before this March 15 massacre, few mass shootings. Here’s what The Atlantic magazine reported after the New Zealand shooting. “This is the deadliest shooting in the modern history of New Zealand, a country where gun violence is rare and annual gun homicides don’t usually reach the double digits. The most recent mass shooting was in 1997, when six people were murdered and four wounded in the North Island town of Raurimu. Until now, the deadliest mass shooting in the country had been in 1990, when a gunman in the small township of Aramoana killed 13 people and injured three. After that shooting, the country amended its laws to limit firearm access. Since then, New Zealand has experienced approximately four incidents of gun violence in which more than five people were killed,” reported Atlantic writer Isabel Fattal the day of the shooting. “According to an open-source database that Mother Jones created, 103 mass shootings have occurred in the United States since 1990, 90 of them since 1997. Overall, the shootings resulted in more than 800 deaths.” Hate-crime shootings are, simply, all too common in our country. The Sikh Temple shooting outside Milwaukee in 2012. The Mother Emanuel AME Church shooting in Charleston, S.C. in 2015. The Tree of Life synagogue shooting in Pittsburgh in 2018. And on and on and on. Of course for victims and survivors, there is little difference between losing a loved one or losing the use of your limbs or organs at school, at a concert, in a movie theater, or in a church. But, somehow, a gunman filled with racist hate entering a place of worship and killing because of the worshipers’ very faith — where believers are on their knees praying, or reciting from the Bible, or welcoming believers into their house of God — somehow, that feels especially dark. There is no telling exactly what will happen with the gun laws in New Zealand. But imagine what the U.S. would have been like today if this country’s leadership had this type of reaction after the 1966 University of Texas Tower shooting, or after Columbine, or Sandy Hook, or Las Vegas or the Pulse? (Let alone in a reaction to all the people shot to death in U.S. murders that are not mass shootings.) How many people who were shot dead would be living full lives today? “To make our communities safer, the time to act is now,” said Prime Minister Ardern on the other side of the world. Let’s hope New Zealand moves beyond “thoughts and prayers,” the phrase our own politicians are quick to spout.  Nirmal Kaur sits below photographs of two Sikh priests killed August 5, 2012. Nirmal Kaur sits below photographs of two Sikh priests killed August 5, 2012. Running late. For most or us, it can mean irritating the more punctual people, or messing up a day’s calendar, or simply triggering feelings of urgency. For some, however, tardiness changed the course of their lives. When it comes to shootings, either random, mass or other types, there is a fine line of fate when it comes to who gets killed or wounded. But even those who are not shot, or do not witness shootings, can be affected. Two families that were late to temple on August 5, 2012, in Oak Creek, Wisconsin, may have avoided death or physical injuries because of being behind schedule. By late morning, six worshipers were dead, including the Sikh temple president and three priests, and four other people were wounded. One of those wounded remains in a nursing home with brain damage more than six years later. Pardeep Kaleka was driving his son and daughter to temple that morning when his 8-year-old daughter announced she had forgotten her Sunday school notebook. He turned the car around and drove home, she ran inside to get the notebook, and they drove back toward the Sikh Temple. Just as he was approaching the highway exit to the temple, however, about a dozen police cars, lights flashing, sped up behind him. He pulled over to let them pass. A former police officer, Kaleka noticed several police jurisdictions were responding. He knew that meant something big was happening. Nirmal Kaur and her family were also behind schedule — due to her own actions. She and her husband, with three small children in tow, reached the temple after the shots rang out. When they arrived “I remember there was all [these] cops blocking all the area,” she said. “If we were not running late, if I was not, you know, spending more time on my makeup — my husband was arguing with me ‘Come on, hurry up,’ — we would’ve been inside there,” she said. “I think about that day all the time. If we were in there, I think, I would have got shot. My husband would have got shot. My kids would have got shot.” That morning at the suburban Milwaukee temple, a neo-Nazi into the white power music scene may have mistook the Sikhs for Muslims. He shot as many people as he could before turning the gun on himself. He died at the scene. The first responding police officer was shot 15 times, and survived, though his injuries forced him to retire from police duty. Pardeep Kaleka knew his parents were inside the temple, but he could not get to them. He received a call from his mother, who spoke quietly because the gunman was still in the temple. She was hiding in the kitchen pantry with about a dozen others. She asked him to get help. He also got a call from his father’s phone — but it was a priest telling him his father had been shot, was in serious condition, and needed help. Because of his former ties with law enforcement, Pardeep was able to speak with the officer in charge. He was finally allowed into the command center at a nearby parking lot, leaving his children with friends. He found his mother, who had escaped the temple with others in an armored police vehicle. She was scared and upset, but not wounded. It was several hours before Pardeep and his brother Amardeep found out that their father, Satwant Kaleka, had been shot dead while fighting the gunman. Nirmal Kaur’s family did not stay at the scene when they learned of the shooting. Stories were flying, and nobody knew exactly what was happening inside the temple, other than someone had been shooting. “We didn’t know what to do,” Kaur said, adding that her young children were frightened. Some members of the temple decided to go out to lunch and stay together for support until answers could be found. But Nirmal wanted to protect her young children from hearing too much. “I told my husband, ‘Let’s get out of here.’ Because the kids were crying. They were getting scared. I said, ‘Let’s take the kids out of here. I don’t want to get them traumatized from this.’” The family drove across town to another Sikh temple in Brookfield, Wisconsin, about 25 miles away. She said people there wanted to hear about what had happened, but she and her husband knew few details. She made sure her children had something to eat after the service, though she and her husband had little appetite. “It was a really sad day,” she said. Since then, many members of the temple have found new directions for their lives. Pardeep Kaleka enrolled in graduate school to become a counselor. He specializes in holistic trauma-informed treatment with survivors of assault, abuse and acts of violence. In his men’s counseling groups, he often addresses male toxicity and anger. He also co-founded the group Serve 2 Unite, which engages youth and communities to create peaceful communities and address violence and trauma. He and former skinhead Arno Michaelis met after the Sikh temple shooting, and they wrote the book, “The Gift of Our Wounds,” about the transformational power of friendship and forgiveness. Kaleka also became a more conscious family man. “I found a new appreciation about fatherhood, and being a husband. And so I started to hug my kids a little bit longer,” he said. “Make love differently — that sounds weird.” Kaleka laughed. “And just generically not taking things for granted. I think a lot of us do that, you know. Because we think we’re going to live ’til tomorrow. And this really showed me that nothing is promised.” Even though Nirmal Kaur had no immediate family members killed that day, the deadly incident that impacted the entire Sikh community pushed her to her re-examine her life and religion. “Since 2012, a lot of changing. I got more involved in my community. I used to stay away. I didn’t care much. Me and my husband got baptized after, in 2015,” said Kaur, who is now the temple community liaison, public educator and greeter. “And then I said to myself, ‘Now I want to do something. I want to educate people.’ It really needs to be done, and we need to do something to show people who we are.” Both Nirmal Kaur and Pardeep Kaleka feel partly responsible for many non-Sikhs in Milwaukee and beyond not knowing enough about Sikhism. She believes if the gunman had known more about them and their religion, he may have left them alone. A chilling fact: The murderer visited the temple a few days before the shooting, and learned the building’s layout for his killing spree. “He took the tour of the temple,” she said, adding that she did not meet him. “All we need to do is talk to them. And sometimes I wish that the shooter came in here, instead of having doubt about who we are, should have talked to us, asked questions. Who you guys are? What are you guys? What do you believe in? What do you guys do for prayer? Nothing. Anybody would answer those questions.” Pardeep Kaleka still mourns his father’s death, yet most days finds himself full of hope. He tries to make the most of every day he is alive — thanks to a forgotten notebook. “We believe in Chardi Kala,” he said of a basic Sikh tenet. That means relentless optimism. Dogs, large or small, service or strictly pets, can be a gun violence survivor’s best friend — a coping tool hidden beneath four paws and a bunch of fur. When Jennifer Longdon was injured by a random shooter in Phoenix, Arizona, 15 years ago, she was paralyzed from the chest down, her life forever altered. Her canine pal Pearl, a Doberman pinscher service dog, helped Longdon negotiate her new world. The two learned together. “I got Pearl as a puppy about a year after my injury. I raised her, I trained her. She was amazing. She actually kind of brought me out of my shell. Because I took her out and walked her,” said Longdon of their ventures into the neighborhood, the human on wheels, the dog loping alongside. “And she was also a bridge to people. So people who didn’t want to talk to me, wanted to talk about the dog. And she became a great connector back to humanity for me.” In addition to helping Longdon ease back into the world, Pearl also gave her human tremendous physical support. “Dobermans have this bad reputation, but they bond to a human. And they’re very smart, and they’re very loyal,” Longdon said. “A lot of other animals are food driven. And a doberman just loves you. They will put down their life for you. Pearl would pick up things that I dropped, she would hold me in my chair, and she watched my transfers. And she would realize before I did that that transfer is not going to work,” she said of transferring herself, for example, from her wheelchair to a couch, or a bed to the wheelchair. “And she would be there and catch me and ease me down, rather than me breaking something.” Before Pearl entered Longdon’s life, Longdon fell out of her wheelchair and fractured a leg. That is not uncommon for people with spinal cord injuries. “Pearl saved me from a lot of fractures. And she would recognize that, ‘You’re not doing so well,’” Longdon said. One of the effects of a spinal cord injury is clonis — a neurological condition that creates involuntary muscle contractions, causing uncontrollable shaking movements. “Sometimes clonis will be so bad that it pulls you out of your chair. And for me, the drugs just weren’t the answer,” Longdon said, adding the condition does not bother her as much as it did in the early days of her injury. “If it got bad like that, sometimes she’d just come and put her head on my leg. And just the warmth and the gentle weight would make it stop.” And then there was the intimidation factor of a 110-pound canine escort. “She was amazing. And everyone who knew her loved her. And she was as intimidating as hell, which didn’t hurt.” Longdon, who goes by Jen, since January 2019 has held a seat in the Arizona State House and is an advocate for gun reform. Pearl died in 2016, and Longdon currently lives with two non-service dogs named Porter and Kuma who valiantly bark at strangers and, Longdon quipped, are both “pro floor-holder-downers.” For another gun-shot survivor, a new puppy helped him move back toward life during a horrific and long physical and emotional recovery. Ron and Nancy Barber lost their golden retriever the year before Ron Barber was shot, and decided, in their 60s, they were done with dogs, certainly with puppies. But that resolution dissolved not long after Barber was hit by two bullets in the January 8, 2011, Tucson, Arizona, Safeway shopping center shooting. District Director for U.S. Congresswoman Gabrielle “Gabby” Giffords, Barber, Giffords and 11 others were wounded by a man obsessed with Giffords. At the public “Congress on Your Corner” event, six people died. For months after the shooting, Barber felt survivor’s guilt, knowing that he was alive while others — including a 9-year-old girl and his assistant, a 30-year-old man, were not. There were months of painful physical therapy, and the emotional work of someone suffering from PTSD. One day at home, he was lying on a chair with his injured leg propped up. His recovery had been slow-going for his body and his mind. “Nancy came home and she said, ‘I’ve got something to show you.’ “She had three puppies in her hand. Three little tiny dots, right? And I said, ‘Oh, Nancy, you didn’t. We said we’d never do this again.’” “Well, there’s only one for us,” Nancy responded, telling Ron to pick between the three. “And I said, ‘Oh, I don’t know.’” “So she put her on my chest. That was the end of that,” Barber recalled, laughing. “And she cuddled me forever. We were inseparable for quite a long time. And I believe that she really had a healing aspect to her.” The tiny bundle of fur named Tipper helped Ron’s wife, too. “If one of us is hurting for whatever reason, you know, she’s all about licking us, making sure we’re okay.” Barber turns back to the dog, a small poodle terrier mix who offers emotional support, but is not a bonafide service dog. “And she’s the best, aren’t you, girl? Yes, she is,” he said, petting Tipper, who perked up. Obviously, they were both still smitten, seven years later. “She was a very important part of me getting better,” he said. For two survivors of the Las Vegas Route 91 Harvest Festival shooting of October 1, 2017, their two pit bulls are there for them during their ongoing recovery. Mindy Scott and her 21-year-old daughter attended the festival, their first concert together after her daughter became an adult. Neither were hit by a bullet, but the aftermath has been intense. Scott’s daughter moved back home for a couple of weeks after the shooting, and it was the dogs the young woman turned to. “When she went home, it was when one of the dogs would walk with her,” Scott said of her daughter’s place, about a block away. “She just did’t feel safe at that time.” Las Vegas is big on fireworks, which can trigger survivors of gun violence. The sound can take them back to the scene of violence and death. New Year’s Eve is often celebrated in Vegas by fireworks over the strip, as is, of course, the Fourth of July. “I hid in my closet,” recalled Scott, a waitress and painter. “I sat with my dogs, my pit bulls, as they snuggled with me.” She and her daughter put on headphones, watched movies on their laptop, and held tight to their rescue dogs. “Roxy just sat there with me. She just laid in my lap,” she said of one of the dogs. “And that’s how we did it through the night,” she said. “It was just getting over that little hump.” For one gun-violence survivor, his dog was there for him after the shooting, and later when he went through his final illness. Now the dog is there for his widow. “Kirra was Bill’s absolute pride and joy,” said Sallie Badger, widow of Bill Badger. A retired Army colonel, he was shot during the 2011 Tucson Safeway shooting, and is credited for helping tackle the gunman that day. “She adored him.” Kirra had been shot and stabbed as a puppy, but found a good life with the Badgers. Bill Badger lived for about four years after the shooting, and the Badgers became advocates for gun reform, traveling across the country to support the cause. A few years after the Safeway shooting, Bill Badger’s health declined. “When Bill was sick, he slept in a guest bedroom because he was in pain and flailing,” Sallie Badger said. “And he said, ‘Is it okay if Kirra sleeps in here with me?’” The huskie-lab mix had never been allowed on the furniture. “I said, ‘Absolutely.’ So she slept on the bed with him. And it was very, very comforting for him.” She paused, and smiled. “I’d go in, and Bill would have this much room [she mimes a few inches] and Kirra was sprawled out, of course.” Bill Badger died in 2015, and Sallie went into mourning. So did his dog. “After Bill died, oh gosh. Kirra went in there and she was in that room 24 hours a day, other than to be taken outside and to eat,” she recalled of the dog in Bill’s final bedroom. “And she was in, this is her pose with the head between her legs and she absolutely would not leave the room. It was the most pitiful thing I have ever seen in my [life]. I didn't know that dogs or any animal could grieve that way.” Sometimes, Sallie would talk to the dog, sharing their mutual grief. “So about three weeks after Bill died I went in there, and I was on my knees next to the bed and I said, ‘Oh Kirra, where's our Bill?’ And she jumped up and went right to the door, flew to the door. I never mentioned his name around her again. But at that point I knew I had to change things. I let this go for quite a few months. She was getting thinner and thinner, losing all this weight.” After six months of the dog mourning, Sallie Badger made a drastic change. She stripped the guest room of bedding, pillows, and mattress. She had the carpet removed and the room redone. “I brought her out and I closed the door and I ended that. And she became my dog. And I had to. I had to. She couldn't, I didn't know how long that would go on. But that was the six-month period. She missed him terribly. And now she is my beloved dog.” Sallie is not someone who appears to live with remorse, but there is one thing she wishes she had done differently. “I really regret that when he was in the hospital at the end that I didn't take her in. They told me I could bring her in. But she's so shy. She’s so skittish. She was an abused dog. “Now most people come, she roars. She really barks. If men come, she really barks. And I'm very happy with that.” Today, Kirra is Sallie Badger’s dog, and the two of them help one another move through the grief of losing their man, Bill.  Pat Maisch, at the "Angel of Steadfast Love" at Kriegh Park in Oro Valley, where shooting-victim Christina-Taylor Green played Little League. Pat Maisch, at the "Angel of Steadfast Love" at Kriegh Park in Oro Valley, where shooting-victim Christina-Taylor Green played Little League. “I’ve read that after a life-changing incident — it doesn’t have to necessarily be seeing six people dead on the sidewalk and 13 wounded — but after a life-changing incident you either become more of who you were — whether to the good, the bad — or you make a 180-degree,” said Pat Maisch, who witnessed the 2011 mass shooting outside a Tucson Safeway store. “And [you] change your life in some way. Good or bad. You know, it’s unpredictable.” For Maisch, the shooting pushed her toward activism, and into public speaking against gun violence and in favor of reforming gun laws. “I think I've become more of who I was, which is compassionate, activist, wanting to see change, working for change,” Maisch said. “It has enriched me in that way, making me more active.” Maisch, who is credited for grabbing the bullet magazine before the shooter could reload, certainly helped stop the rampage on Jan. 8, 2011. Two men tackled the young man who was set on killing Giffords and innocent bystanders. The gunman came to the U.S. Representative Gabrielle “Gabby” Giffords “Congress on Your Corner” event that invited constituents to talk, and or to share grievances and greetings. He shot Giffords in the head, leaving her with a brain injury and partial paralysis, injured 12 others and killed six people, including one of her staffers and others who were waiting in line to speak with their representative. After the shooting, Maisch, then 68, became a vocal member of Everytown for Gun Safety (formerly Mayors Against Illegal Guns). On Jan. 8, 2019, Maisch traveled to Washington D.C., and with Giffords and other survivors of shootings, she stood in solidarity as House Bill 8 was put forward in memory of the Tucson shooting on its eighth anniversary. The bill calls for universal background checks of people purchasing firearms, including sales at gun shows. Maisch has spoken out for gun reform outside National Riffle Association rallies, testified in front of various state senates, and backed the signings of gun legislation. “Until or unless you already know how horrible the gun laws are that the NRA and the gun lobby have been working like for 40 years to quietly change legislators in states [and] then to change them federally, you don't realize how poor the gun laws are and how easy it is to access firearms,” she said. “And when I did find that out, I wanted to help change that. Testifying before the Senate in D.C. was my first opportunity.” Maisch became well known for her advocacy in 2013 after she yelled “Shame on You” at U.S. Senators from the gallery after they refused to pass a bill on gun reform in response to the 2012 slaughter of 20 children and six staff at Sandy Hook Elementary School in Connecticut. After her angry outburst, she was questioned by law enforcement for nearly two hours before being released. In 2016, the silver-haired Maisch was arrested in Washington D.C. after she and other gun-violence protesters staged a sit-in on the floor of the Capitol rotunda. “I used to call myself an advocate. But since things have politically changed so drastically, most of us call ourselves activists now,” Maisch said. “We don’t have the patience for advocacy.” Maisch, who with her husband owns an air-conditioning business in Tucson, also has no patience for the NRA or the politicians who are beholden to the organization. “I call him Mitch-bitch-to-the-NRA McConnell,” she said, referring to Senate Majority Leader Mitch McConnell, who has reportedly received $1.26 billion from the NRA over his political career, and in 2016 said he would not endorse any Supreme Court candidate who did not receive a nod from the NRA. “We have to get the dirty money out of our elections,” she said. In the meantime, Pat Maisch plans to continue her new roll as a gun-reform activist, traveling across the country to advocate on behalf of others, some of whom can no longer speak for themselves. Many are survivors too traumatized to speak. Others are victims who were shot dead. |

AuthorMary Tolan is a fiction writer and journalist. Her first published book Mars Hill Murder, a mystery set in Flagstaff, will be published by The Wild Rose Press in autumn of 2023. Archives

May 2023

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed