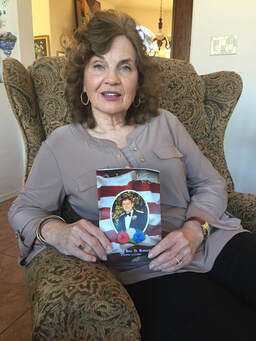

Sallie Badger holding the memorial card of husband Bill. Sallie Badger holding the memorial card of husband Bill. Approximately eight hours after Bill Badger’s head was grazed by a bullet, and after he had tackled the gunman at the Tucson Safeway Jan. 8, 2011, shooting, he and his family were sitting down together at their dining room table, grateful Bill had survived. And praying for the gunman. “He’d been shot in the head, and he’s sitting at the table. We sat here at the table that night, and I said, ‘Let’s pray for that man and his mother and father,’” Sallie Badger told Bill and their son Christian. “Christian, you are the same age. By God’s grace you’re right here with us. We have no idea what went on in his life. All I know is this is what happened, and we have to pray for that family.” Sallie and Bill Badger, a retired Army colonel who was 74 at the time he tackled the shooter, were both significantly impacted by the shooting outside the grocery story at United States Congresswoman Gabrielle Giffords’ Congress on Your Corner event. After the shooting they became advocates for gun reform. Gun-reform organizers especially appreciated Bill Badger’s perspective because of his military background, and because he was a conservative. “He had great presence. He was a wonderful speaker. He stood up one time,” Sallie recalled, “and said, ‘I didn’t have to get shot in the back of my head to know that not every Tom, Dick, and Harry should have a gun in his hand.’” Bill Badger died in 2015 at 78, approximately four years after the Safeway shooting. Sallie believes his deteriorating health was related to the rampage. Within months of the shooting, Badger had a minor stroke near the area of his brain where the bullet had grazed his head, then had a fall — when shooting a rattlesnake on their property —and had spinal surgery. Then, adding insult to real injuries, he developed Parkinson’s disease. Sallie said Bill became frail after a lifetime of health, running or swimming every day. For years, the Badgers had traveled for pleasure, going to Europe for a month every summer as a family, and traveling throughout the U.S. After the shooting, the couple traveled the country for the cause. Journalists and members of the public often referred to him as a hero because of his actions that day. But he declined that title. “Bill immediately corrected them, ‘No. Anyone would have done this.’ And I would say, ‘Bill, anyone wouldn’t have done it.’” She would point out his military training, but told him it was more than that. “‘Most of the people over there, very wisely, if they weren’t shot, were down or behind a post, were hiding, were fleeing,’” she told him. ‘But you didn’t do that. You stepped up because that’s who you are.’” And he would deny it again. Sallie Badger said one result of shootings is the creation of bonds between survivors. She and Bill became part of a growing “family” of shooting survivors. “We got to know the survivors from all these mass shootings. From Sandy Hook, from Aurora, from places that we never, maybe we have heard of before. And they have become our friends. We developed a family outside of our family who we really look at as very close,” she said. “And that’s been a wonderful thing. It’s been wonderful, especially since Bill’s gone.” Bill and Sallie Badger had the reputation of taking action with little fanfare, and of being listened to. This was clear on the day of the shooting. In addition to the fact that Bill Badger took down the gunman that day with the help of another man, little things also reflected the Badger trait of getting things done. When Sallie got the call from Bill that he had been shot, she was at home. She tried to drive to Safeway, but the car battery was dead. So she hitched a ride from her son’s roommate — by this time to the hospital where Bill had been taken — and when she arrived she found that her son had not be allowed in to see his father. “Everything was locked down in town,” she explained. “Everything, every federal building, all that sort of thing, hospitals.” Her son told her the authorities would not let her in to see Bill. “And I said, ‘Christian, do you know who you’re talking to?’” Within a few minutes, she was at Bill Badger’s side. For the first few moments, she could barely speak. “Bill is sitting up, covered in blood. He’d just gotten there. Just pouring, all dripping down his head,” she said. “And he saw me, and just this big smile on his face. And I just couldn’t believe it. And it was really — I really couldn’t even say much of anything.” After Bill Badger received CT scans, the hospital was preparing a room for him to spend the night. But he was having none of that. “‘If I don’t have a concussion or any of that, then I’m going home,’” Sallie remembered him saying. “So they wrapped him up in bandages and he got in the front seat, and I was in back.” Their son drove. Soon, the bandages were gone. “He’s unwinding the bandages. I said, ‘What are you doing?’ He said, ‘I don’t want anybody to see me with this thing on.’ I said, ‘Well, you know the view from back here is not too great.’” She smiled and shook her head at the memory. “This huge wound. But he took that thing off. Yes. And we came home.” Sallie Badger said initially her husband seemed unfazed by the shooting. “He took everything so much in stride,” she said. “It did bother him later. But in that first week or two, I was just amazed at how he handled everything.” Like many shooting survivors, however, it did not prove to be easy — for either of them. After the shooting, Bill became much more protective of his family, and was frustrated when his health began to decline. For Sallie Badger, who does not reveal her age, the shooting altered the course of her life, too. “My life is changed forever because of this. Whether you were there or you were injured or you were a spouse at home. It changes your life.” The surprising part for her was that the shooting impacted her own feelings of security. “There’s no question that it — it just changes everything. It changes your physical and mental outlook. It does,” she said. “Because I wasn’t there, why would I have any lasting issues?” she recalled thinking. She never thought she would be personally affected by post traumatic stress disorder. Now she acknowledges that she has been impacted. “For two years, I knew every single time that I got in my car, other than at my home, that there was going to be a man, that I was going to put the key in the ignitIon and start it, and look, and there was going to be a man with a gun. I knew that. Two solid years of that. Everywhere I went. Every drugstore, every grocery store, the movies, and I’d get in and then I’d look for him.” She recalled one incident where she and Bill were attending their son’s adult city-league basketball game not long after the shooting. A young man wearing a black hoodie ran up behind them as they walked to the building, and Sallie started running away, full speed. “I had no idea I could run that fast. And I’m screaming at Bill to run, run, run,” she recalled. “I ran and got myself in. It was one of the guys playing basketball with our son.” Sallie said the Tucson shooter wore a hooded sweatshirt. While that incident did not affect Bill, other things did. The Badgers went out to dinner at one of their favorite restaurants. They had forgotten about the reenactment of the OK Corral Tombstone shootout. “Bill almost collapsed. We had to leave,” she recalled. “‘Cancel the order. We have to go.’” Like many gun violence survivors, the Badgers were on high alert for months, even years. “You’re constantly vigilant. I’m still very, very hyper-vigilant. And Bill was as well. We were always very comfortable in this home. We sit here alone on two acres.” Sallie Badger recalled traveling out of town after the shooting, without Bill. They talked on the phone. “He said, ‘I really don’t like being here anymore without you. I am so uneasy,’” she said. “And it made me feel terrible that this man that was, you know, the man jumped up and tackled the gunman, is feeling uneasy,” she said quietly. “Those were the things, the everyday things, that just crept in. “It was just an ongoing ripple effect.” And then there was having to reassure others. “People constantly asking, ‘Are you okay?’ ‘Yeah. We’re fine.’ Because everybody says, ‘We’re fine.’ But inside, you’re just always wondering if something’s going to happen.” Like other survivors, the Badgers were offered counseling. They declined, almost without meaning to. In retrospect, Sallie Badger thinks therapy may have helped her husband. “I wish he had. Bill just put it off and put it off and put it off,” she said. “He wanted to do it. But there was always some place to go that was more important for somebody else. ‘They want me to speak here. They want me to come in here. They want me to —’ And he never did it.” When asked why she, too, did not got to counseling, she hesitated. “I don’t know. I don’t know,” she said. “Life goes on.” And she laughed — seemingly at herself. “So I’m doing fine. But I’m also a very, very strong person. When something needs to be done, I take charge and I do it. Bill was the same way,” she said. “He never hesitated in anything. Because you can’t be an Army commander and be, you know, trying to figure out what you’re going to do. “And both of us were the same in that respect,” she said. “And so whatever needs to be done, we just do it.”

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

AuthorMary Tolan is a fiction writer and journalist. Her first published book Mars Hill Murder, a mystery set in Flagstaff, will be published by The Wild Rose Press in autumn of 2023. Archives

May 2023

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed